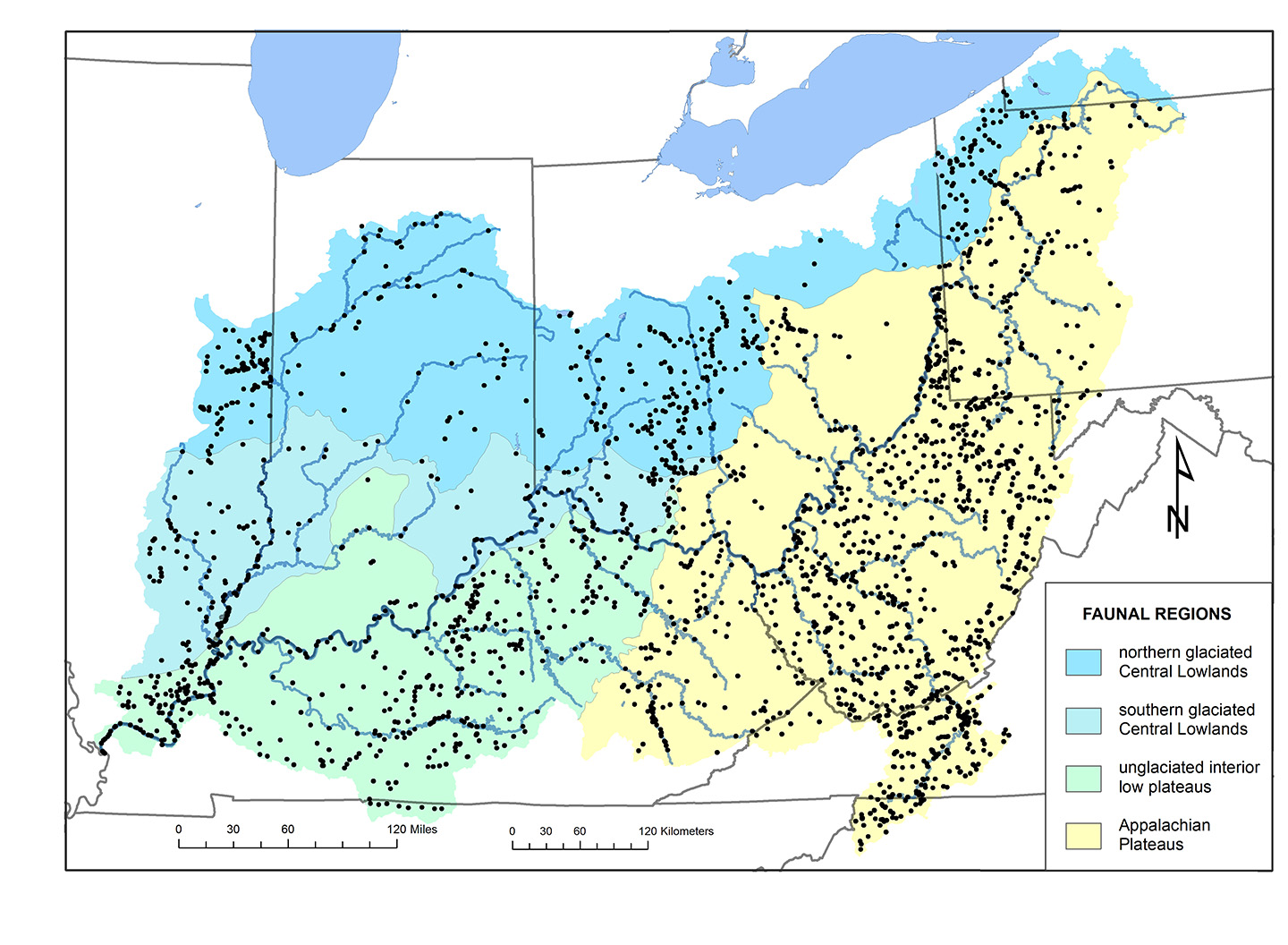

At its broadest scale, this study area can be divided into three vast physiographic regions: the Appalachian Plateau in the east, the Unglaciated Interior Low Plateaus to the south, and the Glaciated Central Lowlands to the north. The Glaciated Lowlands can be subdivided into a northern section covered by the most recent (Wisconsin) glaciation, and a southern section affected by older glacial maxima, but not glaciated during Wisconsin times.

The Appalachian Plateau is a highly dissected region underlain by Paleozoic bedrock of varying lithologies including limestone, dolomite, shale, siltstone, sandstone and coal. The Glaciated Central Lowlands are the opposite – geologically and topographically homogeneous, underlain by plains of glacial till and given over to row crop agriculture, especially corn. The freshwater mollusk fauna of neither of these regions is notably rich, although diversity begins to increase in the lakes and ponds left by the most recent glaciation at the northern margins of the Ohio catchment.

In contrast with the glaciated lowlands to the north of the main Ohio River, the bedrock underlying the Unglaciated Interior Low Plateaus to the south are close to the surface. The rivers of this region, cutting primarily through layers of limestone, sandstone, and shale, often host rich and diverse freshwater mollusk faunas.

Figure 1.

The catchment of the Ohio River basin above

ORM 920.

The first American explorers into the wilderness beyond the Appalachian Mountains (including George Washington in 1770 and Thomas Jefferson in 1781), noted the vast natural resources available in the Ohio River basin. One of the earliest industries was that of salt manufacturing from the brine waters of so-called “burning springs” in the Kanawha Valley of then Virginia (now West Virginia) in the 1790s. The escaping, “inflammable”, gas vapors were eventually harnessed, replacing wood and later coal as the primary fuel for the heating of brine furnaces, giving birth to what would eventually become the natural gas industry (Thoenen 1964).

Most of the catchment was logged and converted to intensive agriculture in the early nineteenth century. The first coal mines were dug in the Pittsburgh area in 1760, spreading into West Virginia in 1810 and Kentucky in 1820. In 1824 the US Army Corps of Engineers made the first improvements to the navigability of The Ohio River, and by the early twentieth century, the entire 981 river miles from Pittsburgh to The Mississippi had been regulated by a series of locks and dams to a minimum depth of six feet (Robinson 1983).

The transportation of goods via water was further bolstered by the building of a network of towpath canals in the 1820s to 1840s across the states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, connecting the Ohio River to Lake Erie via its northern tributaries. While the canals eventually were replaced by railroads, mainline river traffic persisted (Ambler 1932). In 1859, Colonel E.L. Drake had perfected the drilling techniques pioneered by the salt and growing natural gas industry with the first commercial oil well in Pennsylvania, kicking off the petroleum industry by making it widely available for illumination and lubrication, replacing oils derived from the distillation of coal (Thoenen 1964). The attendant industrialization resulted in the development of major commercial centers at Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Louisville.

From the standpoint of American malacology, Ohio was the first frontier. In 1825 Thomas Say packed his library (and his printing press), closed his office door at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and sailed down the Ohio River to New Harmony, Indiana, from whence he continued to describe “new terrestrial and fluviatile shells” until his death in 1834, at the age of 47. And as the muscular new country grew, its center of learning shifted westward. The Illinois Natural History Survey was founded in 1858, with important museums added at Ohio State University and The University of Michigan in the 1870s. Looking back, the early-modern era of American malacology may have reached its zenith when Frank Collins Baker arrived at the University of Illinois in 1918.

Insofar as we are aware, the first comprehensive, regional survey of freshwater mollusks ever conducted in North America was that of F. C. Baker (1902), working from his position at the Chicago Academy of Science. Baker expanded his Chicago-area survey to cover the whole of Illinois in 1906. The literature review of Cummings (1991) returned a remarkable 74 species of freshwater gastropods reported to date from the Land of Lincoln.

Indiana also hosted an early benchmark survey of freshwater gastropods, that of Goodrich and van der Schalie (1944), as well as one of the more modern, that of Pyron and colleagues (2008). Pyron documented a fauna of 36 freshwater gastropods in the Hoosier state, including both the Ohio basin of the south and the Great Lakes basin of the north, noting three local extinctions and two exotic additions. See the essay of 23Jan09 on the FWGNA blog for a more complete review of the Pyron survey results (Dillon 2019a).

The malacofauna of Kentucky is apparently quite diverse but poorly known. Bradley Branson published a series of local surveys (Branson & Batch 1981a, 1981b, 1982a, 1982b, 1983) as well as a key to 60 species and subspecies of freshwater gastropods either “known from Kentucky” or “which should be here but which have not been reported” (Branson 1987). But his actual field observations confirmed only 28 species in the waters of the Bluegrass state, across both the Ohio and Cumberland basins combined (Branson, Batch & Call 1987). Subsequent local surveys (Brown et al. 1998, Evans 2012) have augmented this list only marginally.

The freshwater gastropod fauna of the state of Ohio is well-surveyed, although not especially well-documented. LaRocque (1959) tallied an astonishing 165 nominal species and subspecies of freshwater snails inhabiting the Buckeye State, employing as he did an archaic taxonomy difficult to translate into the modern vocabulary. Beginning in the early 1970s, D. H. Stansbery and Carol Stein amassed a comprehensive collection of freshwater gastropods at The Ohio State Museum in Columbus, an effort that continues to the present day under their successors. The effort has as yet yielded no publication, however.

West Virginia is almost unexplored malacologically. Schwartz & Meredith (1962) reported just four freshwater gastropod species inhabiting the entire Cheat River system, a tributary of the Monongahela in northeastern West Virginia, attributing the lack of diversity to acid mine pollution.

The situation in Pennsylvania is much better. R. R. Evans & S. J. Ray published a freshwater gastropod checklist in 2008, followed by an original field survey in 2010. The 2008 work brought an old and scattered literature together with a modern review of museum holdings, yielding a remarkable 63 nominal freshwater gastropod species for the Keystone State, of which 43 might be recognized as specifically distinct inhabitants of Ohio drainages. The 2010 work followed with a field survey of 398 lotic water bodies across the state (no ponds, lakes, or marshes), returning 37 nominal species, 20 of which are specifically distinct inhabitants of the present study area. Much of the discrepancy between the 63 species expected from the 2008 checklist and the 37 species observed in the 2010 field survey probably arises from the exclusion of lentic waters from the latter, but not all. See my essay of 22June10 for a more complete review (Dillon 2019b).

> Methods

The version of the FWGO database online as of 5/2022 contains 5,367 records. Of the total, approximately 37% are from museums, 35% from natural resource agencies, and 26% from personal collections (Table OH1). Ultimately our survey covered approximately 2,550 unique sample sites, located throughout the Ohio drainage above the mouth of the Tennessee/Cumberland, in all ecoregions, all subdrainages, and all counties (Figure 1).

The natural resource agencies contributing data were, in order of their totals, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WV-DEP, 784 records), the Kentucky Division of Water (KY-DOW, 529 records), the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO/MUMCO, 259 records), the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA-DEP, 110 records), the Virginia Department of Natural Resources (VA-DNR, 67 records), the North Carolina Department of Water Quality (NC-DWQ, 43 records), and the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (VaDCR, 17 records).

The WV-DEP Division of Water and Waste Management, Watershed Assessment Section in Charleston, WV, conducts a regular schedule of benthic macrobenthic surveys in connection with a variety of water quality monitoring responsibilities (Pond et al. 2013). Their standard approach is to select a 100m “assessment reach,” within which four kicknet samples of one-quarter square meter each are collected. These four samples are combined into a composite jar, from which 200 organisms are randomly subsampled, counted, and identified.

We reviewed all macrobenthic samples collected by the WV-DEP 1996 – 2015 from which gastropods of any species were recorded. Eliminating date-duplicates and samples taken in close proximity yielded 1,285 qualifying samples, which we individually inspected in October 2016. Setting aside lost, damaged, or otherwise unidentifiable specimens yielded 1,106 records from the state of West Virginia, 784 of which were taken from the Ohio River drainages under study here.

The KY-DOW also conducts a great variety of macrobenthic surveys, including their Reference Reach Program (REF, targeted toward least-impacted sites), their Probabilistic Surveys (PRB, randomly chosen for trend analysis) land their Targeted Sites program (TMD, selected to calculate maximum daily load).

In high-gradient streams, KY-DOW personnel use a four-kick composite riffle sample (similar to WV-DEP) plus a multihabitat sample taken with a D-frame net. The multihabitat component combines samples from woody debris, large boulders, emergent vegetation, leaf packs, depositional areas, and so forth. In low-gradient streams a 20-jab method is used, again with a D-frame net focused on the more productive habitats. Macrobenthic samples (regardless of purpose or method of sampling) are (generally) retained for five years. See Brumley et al. (2015) for details.

Review of the KY-DOW database returned 910 freshwater gastropod records sampled from 2010 – 2014, over all projects and methods, over all waters of the commonwealth. Our visits to the laboratories of the Kentucky DEP Division of Water in Frankfort in October 2016 and January 2017 added some samples collected as early as 2004. Subtraction of duplicate samples and samples unidentifiable due to loss, breakage or juvenile size ultimately yielded 529 qualifying records from the Ohio drainages under study here.

The Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO) is an interstate agency charged with monitoring water quality in the main Ohio River. They have monitored the macrobenthic community since 1964 using a variety of methods, including Hester-Dendy (1962) samplers (suspended units of Masonite cardboard plates and spacers), as well as a qualitative multihabitat approach (Orsanco 2017). We were gifted 142 ORSANCO samples in 2013 by R. W. Taylor, together with 117 other (“MUM”) samples personally collected either by himself or by T. G. Jones & C. D. Swecker 1988 – 2007.

See the FWGMA methods section (FWGMA) for details regarding our PA-DEP samples, the FWGVA methods (FWGVA) for specifics regarding the VA-DNR and VA-DWQ samples analyzed here, and the FWGNC methods section (FWGNC) for more on the NC-DWQ.

The museums contributing data to the present survey were, in the order of their totals, the Ohio State University Museum of Biological Diversity in Columbus (OSUM, 908 records), the Illinois Natural History Survey in Champaign (INHS, 606 records), The Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh (CM, 360 records), the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Drexel University (ANSP, 89 records), and others (USNM, VMNH, FMNH) 45 records together.

Museum collections are typically biased in favor of larger and more conspicuous species (especially pleurocerids), species that are perceived to be rare or endangered, and invasive or accidental species, such as those collected on the margins of their ordinary ranges. A large fraction of most museum collections will be old, often with only approximate locality data, and although certainly of historic value, not useful for the modern survey that was our aim here.

We began all our museum surveys by carefully screening the collection databases, eliminating all undated lots or lots collected prior to 1955. We required that each museum record be plottable – with locality data of sufficient quality to permit the estimation of latitude and longitude coordinates. We then inspected each qualifying museum lot personally on site, to confirm its specific identification.

Our review of the freshwater gastropod collections held by the Ohio Museum of Biological Diversity took place in June 2014. Because the bias toward pleurocerid snails in the greater OSUM collection seemed unusually pronounced, we elected to focus on lots with OSUM site numbers, where teams from the museum made comprehensive collections 1955 – 1994.

Quantitative and semi-quantitative sampling approaches, such as those employed by state natural resource agencies in connection with their routine water quality monitoring responsibilities, demonstrate a well-documented bias against rare species. Thus, we also reviewed the larger OSUM collection as a whole, selecting and incorporating into our database modern, well-documented lots of uncommon species.

Our initial review identified 1,260 qualified lots from the six primary states of the Ohio River Basin: PA, WV, OH, Ky, IN, or IL. After verifying the identifications, we screened these records to remove duplicates. As a rule of thumb, where we found more than one record of a species collected from the same waterbody, within a 5 river-mile (8 km) radius, we removed the older record. A total of 908 OSUM records ultimately qualified for inclusion in the FWGO database.

A similar approach was followed at the Illinois Natural History Survey, which we visited June 19 – 21, 2017. We initially identified 3,433 freshwater gastropod records from the state of Illinois, 1955 to present, with lat/long coordinates. This number was reduced to 2,541 by the removal of duplicates, and further reduced to 606 by focusing exclusively on collections from drainages of the Ohio above ORM 920.

We visited the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh July 17 – 18, 2012, ultimately qualifying 876 records of freshwater gastropods collected from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania after 1955, with good data. The great majority of the CMNH records were collected by Evans & Ray (2010), effectively merging that earlier survey into the present one. A total of 499 records came from the Atlantic drainages of Pennsylvania, covered by the FWGMA elsewhere on this site. A small subset of 17 were collected from drainages of the Great Lakes, leaving 360 Ohio River drainage samples to be covered here.

See the FWGMA and FWGVA sites for details regarding our smaller samples from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and the US National Museum (Smithsonian), and the Virginia Museum of Natural History.

Finally, original field surveys were conducted to supplement the collections already held by museums and natural resource agencies, using simple untimed qualitative searches (Dillon, 2006). Subtotals of 72 personal collection records were contributed by WKR sampling in Ohio 2013 - 2016, 270 by MP sampling in Indiana 2006 – 2008, 378 by RE sampling in Kentucky 2006 – 2011, and 668 by RTD sampling basin-wide 1976 - 2022. The Pyron records have been published by Pyron et al. (2008).

We have made efforts to sample personally all USGS hydrological units distinct at the 8-digit level in all counties in all states. Our emphasis has generally been directed toward lakes, reservoirs, and other lentic habitats, which have tended to be under-sampled by water quality monitoring agencies, as well as marshes, swamps, springs, vernal habitats, freshwater tidal estuaries, and the larger, deeper rivers. The lentic environments and the larger rivers have often been sampled by kayak.

A map (in PDF format) showing the distribution of all 2,550 of our unique sample sites is available as Figure 1. No “absence stations” are shown. If freshwater gastropods were not collected at a site, then no record resulted. Our entire 5,367 record database is available (as an excel spreadsheet) from the senior author upon request.

The taxonomy employed by the FWGNA project is painstakingly researched, well-reasoned and insightful. Needless to say, it often differs strikingly from the gastropod taxonomy in common currency among casual users and most natural resource agencies. First-time visitors looking for information about particular species or genera might profitably begin their searches with a check for synonyms in our alphabetical index.

> Results

The 72 species and subspecies of freshwater gastropods we have confirmed from waters draining into The Ohio River above the mouth of the Tennessee/Cumberland are listed in Table Bi1, both in [pdf] format and as a simple, sortable [excel] spreadsheet. They are figured in the FWGO gallery and distinguished on the FWGO dichotomous key. Ecological and systematic notes for each species and subspecies are provided on dedicated pages, together with regional distribution maps. Their distributions and abundances on a continental scale are analyzed in our sections on Biogeography and Synthesis.

> Acknowledgements

The following colleagues graciously hosted us in the museums: Tim Pearce at the CMNH in Pittsburg, the late Tom Watters at the OSUM, Gary Rosenberg, Paul Callomon, Amanda Lawless at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and Bob Hershler and Chris Meyer at the US National Museum. We thank Mr. Tony Shaw, Ms. Molly Pulket, Mr. Rick Spear, and (especially) Mr. Dan Boger of the PA-DEP in Harrisburg. And special thanks to Dr. Ralph W. Taylor who provided our ORSANCO/MUM samples and consulted with us early in this effort.

Rick Relyea and Andy Turner were marvelous hosts at the University of Pittsburgh's Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology during the summer of 2012.

> References

Ambler, C.H. (1932) A

History of Transportation in the Ohio Valley. Arthur H. Clark

Company. Glendale, CA. 465pp.

Baker, F.C. (1902)

The Mollusca of the Chicago area. Part 2, The Gastropoda.

Chicago Acad. Sci. Natl. Hist. Survey 3: 131-410.

Baker, F.C. (1906)

A catalogue of the Mollusca of Illinois. Bulletin of the Illinois State

Laboratory of Natural History 7: 53-136.

Bickel, D. (1967)

Preliminary checklist of Recent and Pleistocene Mollusca of Kentucky.

Sterkiana 28: 7-20.

Branson, B.A. (1987)

Keys to the aquatic Gastropoda known from Kentucky. Transactions of the

Kentucky Academy of Science 48: 11-19.

Branson, B.A. &

D.L. Batch (1981a)

The gastropods and sphaeriacean clams of the Dix River system,

Kentucky. Transactions of the Kentucky Academy of Science 42:

54

– 61.

Branson, B.A. &

D.L. Batch (1981b)

Distributional records for gastropods and sphaeriid clams of the

Kentucky and Licking rivers and Tygarts Creek drainages,

Kentucky. Brimleyana 7: 137 – 144.

Branson, B.A. &

D.L. Batch (1982a) The Gastropoda and Sphaeriacean clams

of

Red River, Kentucky. Veliger 24: 200 – 204.

Branson, B.A. &

D.L. Batch (1982b) Molluscan distribution records from the

Cumberland River, Kentucky. The Veliger 24:351-354.

Branson, B.A. &

D.L. Batch (1983)

Gastropod and Sphaeriacean clam records for streams west of the

Kentucky River drainage, Kentucky. Transactions of the Kentucky Academy

of Science 44:8-12.

Branson, B.A., D.L. Batch

& S.M. Call (1987)

Distribution of aquatic snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in Kentucky with

notes on fingernail clams (Mollusca: Sphaeriidae:

Corbiculidae).

Transactions of the Kentucky Academy of Science 48: 62 – 70.

Brown, K.M., J.E.

Alexander & J.H. Thorp (1998)

Differences in the ecology and distribution of lotic pulmonate and

prosobranch gastropods. American Malacological Bulletin 14:

91 –

101.

Brumley, J., J. Schuster,

K. McKone, R. Evans, M. Arnold, A. Keatley, L. Hicks, & P.

Goodman (2015)

Methods for sampling benthic macroinvertebrate communities in wadeable

waters. Kentucky Department of Environmental Protection,

Division

of Water Document DOWSOP03003, 19 pp.

Cummings, K.S. (1991)

The aquatic Mollusca of Illinois. Illinois Natural History

Survey Bulletin 34: 428-437.

Dillon, R.T. (2006)

Freshwater Gastropods. pp 251 - 260 in Sturm, C.F.,

T.A.

Pierce & A. Valdes (eds.), The Mollusks: A Guide to Their

Study,

Collection and Preservation. American Malacological

Society, Pittsburgh, PA. 445 pp.

Dillon, R.T. (2019a)

The freshwater gastropods of Indiana. Pp 215 - 218

in The Freshwater Gastropods of North America, Volume 4.

Essays on Ecology and Biogeography. FWGNA Press,

Charleston.

Dillon, R.T. (2019b) Unlocking

the Keystone State. Pp 219 - 222 in The Freshwater

Gastropods of North America, Volume 4. Essays on Ecology and

Biogeography. FWGNA Press, Charleston.

Evans, R. (2012)

Recent monitoring of the freshwater mollusks of Kinniconick Creek,

Kentucky, with comments on potential threats. Walkerana 15:

17 –

26.

Evans, R. & Ray,

S. (2008)

Checklist of the freshwater snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of

Pennyslvania, USA. Journal of the Pennsylvania Academy of

Science

82: 92-97.

Evans, R. & Ray,

S. (2010)

Distribution and environmental influences on freshwater gastropods from

lotic systems and spring environments in Pennsylvania, USA, with

conservation recommendations. American Malacological Bulletin

28:

135 - 150.

Goodrich, C. &

van der Schalie, H. (1944) A revision of the Mollusca of

Indiana. American Midland Naturalist 32: 257-326.

Hester, F.E., and J.S.

Dendy (1962) A multiple-plate sampler for aquatic

macroinvertebrates. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society

91:420–421.

LaRocque, A. (1959)

Checklist of Ohio Pleistocene and living Mollusca. Sterkiana 1: 23-49.

ORSANCO

(2017) Biological Programs Standard Operating

Procedures.

ORSANCO, Cincinnati, OH. 60 pp. Appendices E, F, G, and H.

Pond, G.J., J. E. Bailey,

B.M. Lowman & M.J. Whitman (2013)

Calibration and validation of a regionally and seasonally stratified

macroinvertebrate index for West Virginia wadeable streams.

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 185: 1515-1540.

Pyron, M., Beugly, J.,

Martin, E., & Spielman, M. (2008) Conservation of

the freshwater gastropods of Indiana: Historic and current

distributions. Am. Malac. Bull. 26: 137 - 151.

Rosewater, J. (1959)

Mollusca of the Salt River, Kentucky. Nautilus 73: 57-63.

Schwartz, F.J. &

W.G. Meredith (1962)

Mollusks of the Cheat River watershed of West Virginia and

Pennsylvania, with comments on present distributions. Ohio

Journal of Science 62: 203 – 207.

Thoenen, E.D. (1964)

History of the Oil and Gas Industry in West Virginia.

Education Foundation Inc. Charleston, WV. 429pp.